Educated to Bits!

Our education systems and teachers' training not only fail our children for the future, they institutionalise them to compartmentalise, fragment, and exchange their responsiveness to Earth for profit

Our education systems and teachers' training not only fail our children for the future, they institutionalise them right now to compartmentalise, fragment, and exchange their responsiveness to their Earth for profit within consumerism, addictions and the systems set up to sustain them…. Including social media.

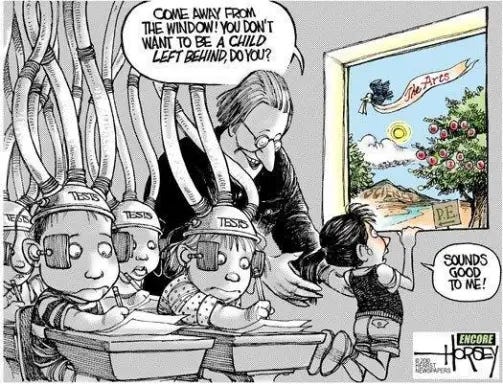

I am including links to two Substack blogs here. The first is that of artist and systems thinker, Christopher Chase. His illustrated piece shows how western schooling trains us to not just separate but to compartmentalise what is known. One of the reasons I moved from clinical psychology to Earth-centric transformative learning was to be able to draw on multiple fields of knowing in an integral way. Christopher points out that such fragmentation is structured to meet the needs of the more powerful, and of a consumer culture, not the needs of the learner.

Compartmentalising in education

The second link is to Jennifer Browd’s guest article in The R Word. She speaks to education as indoctrination. It is intended to do what it does, i.e. make us obedient unquestioning workers in an extractive capitalistic system and thus increase our ecological footprint. Her piece goes to the heart of what sort of profound change we need right now to access and rekindle that Earthcentric child in each of us.

Not being sent to formal school until I was eight, may have saved me from some of the compartmentalisation and indoctrination of western education.

I was reading by four. My parents’ library in Ghana was limited but full of geography and nature books, a range of Irish writers and poets, some books on history from left-leaning authors and lots of popular detective novels, many unsuitable for a child. I learnt the names, habits, and habitats of most of the animals, reptiles, birds and insects around me from the books and the land and people who cared for me. Being daily in the wilds with my father, a geographer and educator in the Ashanti region, also helped me to see the land and waters around us. From my mother, I learnt art and social skills, coloured by a mixture of colonialism and embodied wisdom. I knew the songs from almost every musical of the late fifties and early sixties from Mammy’s singing along to her record collection and from her passion for Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone and Billy Holiday. This raised early awareness of racial inequities and of women’s heartache though the African women locally were very different. They were the “market mammies”, leaders of commerce and of family life. Local calypso, highlife dance music and traditional tribal drumming at weekly gatherings contributed to my cultural exposure. I loved rhythm. My mother who had worked in the Civil Service in Dublin Castle, also instilled “manners”, the correct way to set a dinner table, love of fashion and how to welcome guests from many backgrounds into our home. Having both my parents speak Irish at home was an invisible and invaluable part of my early learning. Only recently have I understood how understanding and feeling Irish Gaelic’s six words for up and down in relation to the earth and each other, shaped my complex understandings of “power over” and “power with”, personally and collectively. (See “Irish before Celts, Colonisation and Christianity”)

Being daily in the wilds of coastal and rain forested West Africa, grounded my whole sense of myself in the natural world around me. Being close to the Fanti and Ashanti who took care of me also meant seeing women as central to spirituality, as the keepers of the marketplace and as comfortably embodied, sensual, joyous beings who loved to move. They balanced huge loads on their heads like queens with enormous crowns. Their little children were always close, bound to their backs in bright cloth or in touch beside them much of each day.

None of this prepared me for the experience of institutionalised education when I was sent back to the damp greyness of Belfast Northern Ireland at age eight. Apart from missing the vibrant wildness of my environment, I missed my family, and the culture and people of West Africa. Rote learning while confined in a desk had little attraction. Even at eight, there was a lot of shaming. In the Holy Family primary school close to my grandmother’s row house in a Belfast Catholic ghetto, I was moved quickly through early grades. Missing home, family and my whole living context, I sucked my thumb.

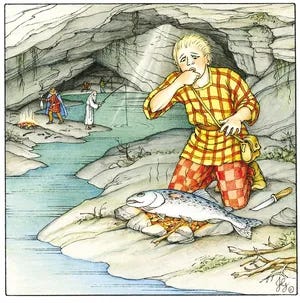

Crying from the name calling, I was deeply comforted by grandmother’s tale of the Salmon of Wisdom being barbequed by a bard for his own enlightenment by his young apprentice, Finn. When hot fat splattered young Finn, he sucked his thumb. All the knowledge held by that Salmon…who had eaten hazelnuts in the stream below the Tree of Wisdom, then entered Finn rather than the bard. Later, as I trained in child development, hypnosis and trauma healing, I recognised that child thumb-sucking response as protective mild dissociation, self-hypnosis and trauma healing. By eleven, I passed the exam that opened the door to secondary school… in a convent.

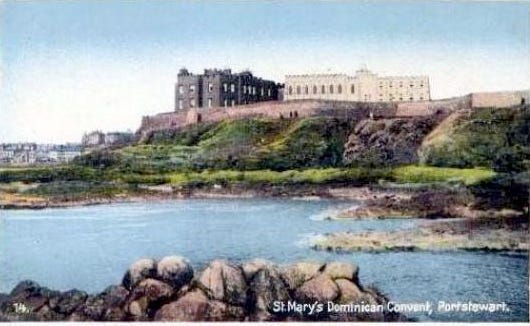

That was not the end of shaming and demeaning. Being locked up with the nuns in a cold boarding school high above the wild North Atlantic for five years, being called “savage” because I climbed over the walls to rescue injured birds and was from Africa, being called “whore” for hiking up my school uniform and because girls were considered “an occasion of sin”…none of this endeared me to school. In fact, I have always had an ambivalent response to my “good British education” right up to the doctorate in clinical psychology in Canada in the 90s. Having to frame “trauma” and “breakdown” as “mental illness” rather than understandable responses to what was happening around us, still makes no sense to me.

From my first day in that residential school, it seemed that even at eleven, I was eager to know how people and their history affected each other. When asked by the Mother Superior that morning what I wanted to be, I said: “A psychologist or an archaeologist.” I knew I wanted to dig deeply into people’s history over generations. Those early detective novels whet my appetite for piecing together over time what had happened to make people do what they were now doing, especially if it was unjust. At the time that is what I thought psychologists and archaeologists did: it is what I had been taught. Mother Laurentia snapped back at me, “Child, you cannot spell those let alone be them. You will be a nurse or a teacher like the rest of us!” It was enraging even before any of my feminist consciousness had set in. I knew how to spell those words!

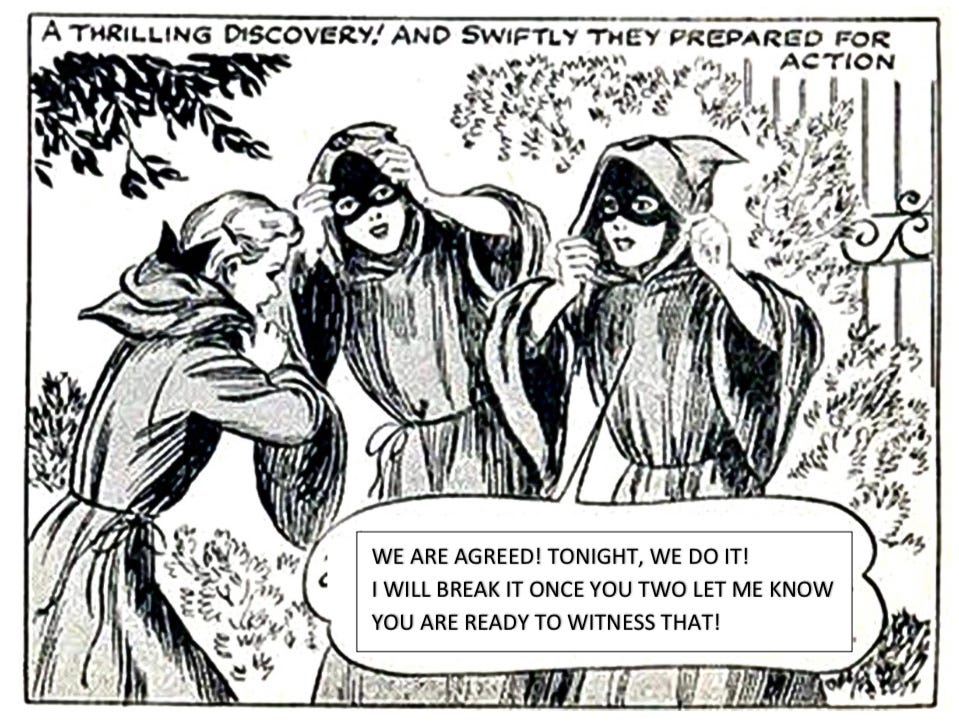

Forming the Silent Three with two eleven-year-old friends in my dormitory, was my first foray into counselling others… and into applying that sense of outrage and thirst for justice within my local community of boarders. None of the nuns seemed approachable when we were upset or saw our friends mistreated.

Girls put their problems into a bag hung on the hot water tank by the bathroom in the first years’ dormitory. We, the Silent Three, wrote or acted on issues talked over together late at night. Removing and breaking the plastic hairbrush as it was being used by Sister Theresa to hit a girl who bedwet, was one such action. Being agreed, fearless and supported by those we knew, made a difference. Sister Theresa said and did nothing. There was no more physical punishment or shaming in the dorm that year. The Silent Three remained active and seemingly effective for two years.

The reality is children can integrate information, draw on their own collective intelligence and move into creative and effective action. When they are educated in integral and meaningful ways that foster mutuality in relationship and encourage them to form a learning community, when classrooms are no longer structured with everyone looking to the authority at the ‘top’, when feelings and their life experiences are honoured rather than discouraged or dismissed, isolation is broken and fear reduced. There is a release of synergistic creativity.

Look next for a primer on using circles to address complex emotions, help integration, draw on the collective intelligence present and provide grounded hope in “Educating Our Children on Climate Crises”

i See “Belfast”, Kenneth Branagh’s brilliant film of the Protestant streets of the same ghetto three streets away.

Here are the direct links to the Chris Chase and Jennifer Browdy articles. The Substack hyperlinks only go to the host pages. Thank you to the readers who pointed this out...

https://creativesystemsthinking.wordpress.com/2019/06/08/how-we-learn-to-compartmentalize/

https://rword.substack.com/p/education-as-indoctrination-vs-education

Forgive the delay in getting this post out. Family changes, computer glitches and beginning to write a longer piece, now the writing block has ended with Resonant Earth. "Full of Your s/Self" integrates the healing work my late partner Ed O'Sullivan and I did through the mycelium network of kindred spirits that is the Spirit Matters and Transformative Learning Community and our love.